When Paris burned

Inequality In 2005, two innocent teenagers were electrocuted while hiding from police, triggering a revolt in France’s low-income suburbs, the banlieues. The last decade shows that post-riot policies have solved nothing.

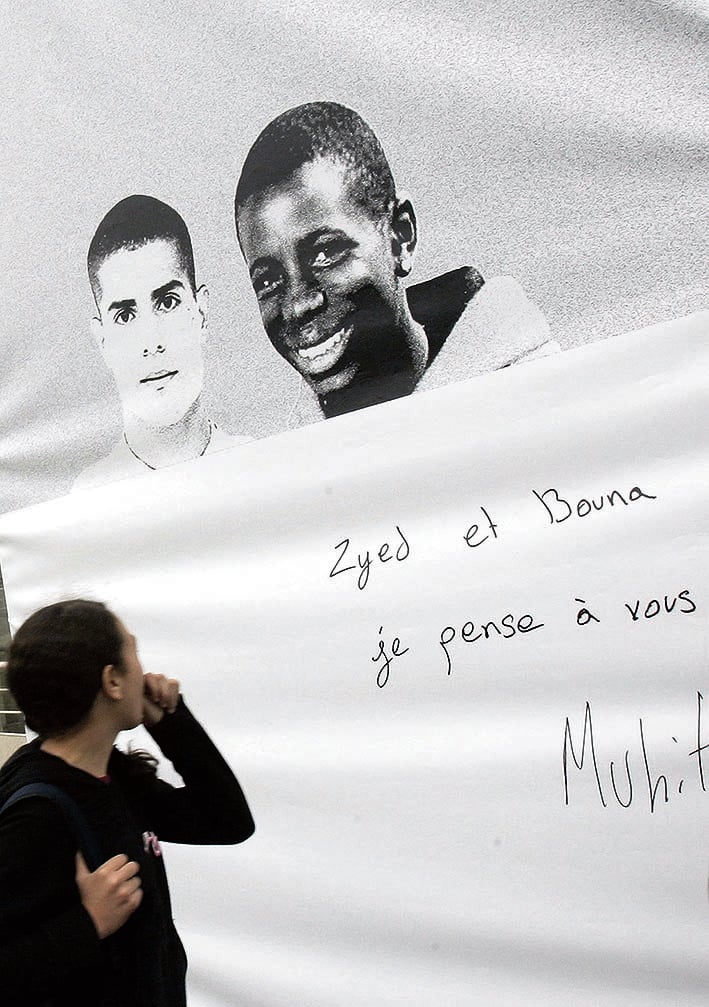

Le Bourget, Paris, the riots on Nov. 4 2005 – AP

Le Bourget, Paris, the riots on Nov. 4 2005 – APInequality In 2005, two innocent teenagers were electrocuted while hiding from police, triggering a revolt in France’s low-income suburbs, the banlieues. The last decade shows that post-riot policies have solved nothing.

Ten years ago, on Oct. 27, 2005, Zyed Benna and Bouna Traore, two teenagers aged 15 and 17, were electrocuted in the Parisian suburb Clichy-sous-Bois in an electrical box where they had taken refuge to escape the police, even though they had done nothing wrong.

In response to these deaths, the banlieues exploded, from the outskirts of Paris to other French cities. For 20 days, rioters burned cars and destroyed symbols of government (libraries, schools, gyms) and capitalism (shopping centers). The then prime minister, Dominique de Villepin, declared a state of emergency, something that hadn’t been done since the war in Algeria. In three weeks, there were 4,000 people arrested and 600 charged with crimes.

A few months ago, in May 2015, the two police officers involved in the hunt for Zyed and Bouna were acquitted of “non-assistance to a person in danger,” even though a phone call recording showed the officers were well aware of the risks faced by young people hiding in the power substation.

Distrust of the police — for fear of officers and their constant surveillance, particularly among immigrants and Muslims — is one of the heaviest legacies of 2005.

A decade later the situation has not improved. The recent increase in illegal trafficking, one of the effects of the economic crisis, and the greater visibility of Islam have created a new state of fear that strains relations between different neighborhoods of cities.

Nicolas Sarkozy, when he was interior minister, had fanned the fire, promising to free the people of Argenteuil from “scum,” making “use of Karcher” (a brand of pressure washers). As president, he continued to distill the poison of stigmatization.

François Hollande has promised interventions and has achieved some gains in combatting discrimination, but the operation ran aground against the Valls government. Prime Minister Manuel Valls himself, however, has spoken of “territorial, social and ethnic apartheid” and yesterday, October 26, after a symbolic inter-ministerial meeting in Mureaux, promised to come down on municipalities that refuse to build public housing.

But politicians continue to perpetuate the “us” and “them” mentality that undermines French society, fomenting mutual distrust. People in the suburbs have consistently said they lack one thing: “respect.”

In 10 years, there have been various interventions in the banlieues, starting from housing. The government spent €48 billion for urban renewal, tearing down 151,000 derelict homes in 600 districts, renovating 320,000 of them and building 136,000. Another 50,000 are slated for demolition and reconstruction, and there’s a plan to strengthen the transportation network as part of a “Grand Paris” project.

These policies have changed the set design but not the script, despite some initiatives in schools to elevate the brightest students, the creation of agencies to promote investment (even the United States participated) and laws that recognize the reality of discrimination.

But the economic crisis of 2008 hit the lower classes especially hard, mainly in the suburbs, which over the years have lost the social cohesion once created by working in the same factory or joining the union.

The figures are dramatic

In the suburbs, the average income is 56 percent of the national average, unemployment is 10 points higher (20 points for people younger than 25) and job insecurity is rampant (7.5 percent of the department of Seine-Saint-Denis receives income subsidies).

If you take the RER from Luxembourg station in central Paris to La Courneuve, a northern suburb, you lose 15 years of life expectancy.

More than half the children living in working-class areas are below the poverty line, and in Seine-Saint-Denis, infant mortality is 40-50 percent higher than in the rest of France.

Despite all these difficulties, the lower class has shown resistance.

The highest rate of business creation is in the suburbs. The young people study; more than 50 percent of the children of workers graduate from high school, and many continue to universities.

Lawyers, doctors, teachers, researchers and managers are more and more coming from these struggling neighborhoods.

The Bondy Blog, founded in 2005, continues to tell stories of battles, successes and defeats of a French youth born in the banlieues, which seven out of 10 French still consider “dangerous.”

- Originally published in Italian at il manifesto on Oct. 27 2015

I consigli di mema

Gli articoli dall'Archivio per approfondire questo argomento